Annika Mozer

Privat

Privat

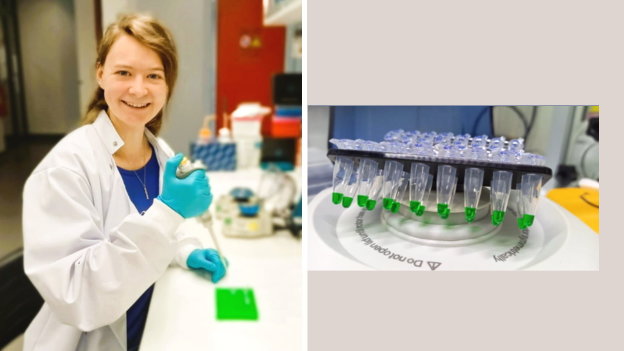

Annika Mozer at the National Fish and Wildlife Forensic Laboratory in Ashland

“This project made it clear to me once again that the illegal trade in wild animals does not respect political boundaries, which means that our cooperation in stopping the illegal trade in wild animals should not do so either! I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the host institutions and Prof. Bingel Scholarship by the DAAD-Stiftung for giving me this unique and incredible opportunity and its associated experiences.”

In the field of wildlife protection, the illegal trade in animal products remains a significant challenge that requires innovative approaches to prevention and control. Annika Mozer researched this topic with the Prof. Bingel Scholarship by the DAAD-Stiftung.

One can tell her enthusiasm for her research work and her aim to contribute to change in the descriptions of her stays in the U.S. and Vietnam:

USFWS (National Fish and Wildlife Forensic Laboratory of the United States Fish and Wildlife Services in Ashland)

I was testing molecular markers involving hornbills (Bucerotidae). The beaks of hornbills are often traded for decorative purposes; those of the helmeted hornbill (Rhinoplax vigil) in particular are frequently carved and sold as ‘red ivory’. There are some 60 different species of hornbill, and not all species are protected under international trade legislation (CITES – Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna), so customs officials need morphological guidelines to enable them to quickly, efficiently and reliably differentiate between legal and illegal species.

IEBR (Wildlife Forensic Laboratory of the Institute of Ecological and Biological Resources of the Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology in Hanoi)

My time spent conducting research at IEBR took place from 15 March to 31 March 2024. Here too I was testing DNA markers, although in this case involving species of Vietnamese salamanders (Tylototriton spp. and Paramesotriton spp.). These salamanders are often poached in Vietnam and then end up as illegal pets around the world. Germany in particular is one of the major markets within the EU for illegally traded reptiles. There is therefore a need for morphological tools here too; to enable these species to be identified, but also for example to conduct population studies to assess the level to which salamanders are at risk.

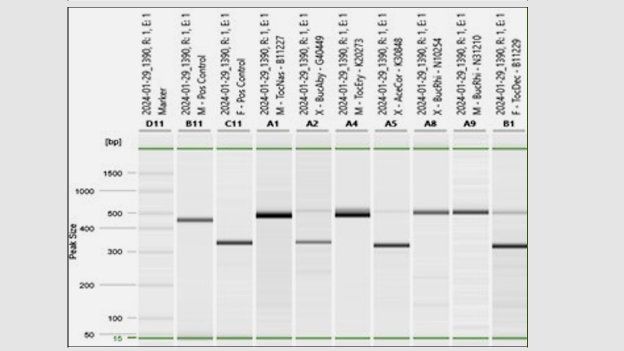

Both projects involved me working with archive material, since there was insufficient time to gather sample material (including permissions and the like). I was unable to discern a cultural difference in the approach to species protection; both countries are motivated in their implementation of species protection laws, although there were financial differences that ultimately have a major impact on the analyses thus facilitated. Yet this project made it clear to me once again that the illegal trade in wild animals does not respect political boundaries, which means that our cooperation in stopping the illegal trade in wild animals should not do so either! A typical day in the laboratory started with an extraction, whereby the samples may have already been in lysis overnight. Then I prepared and started the PCR. As this was running, I prepared, processed or evaluated other samples. A gel electrophoresis was conducted after the PCR to see if it had been successful. Then the sequencing was prepared, and this reaction was also started. Once sufficient samples were ready for sequencing detection in a capillary electrophoresis, I then started a disc run that usually ran over night.

Privat

Left: Silver-cheeked hornbill (Bycanistes brevis). Right: Great hornbill (Buceros bicornis)

Successful outcomes

USFWS: Here I tested various DNA markers to enable consistent identification of hornbill species by comparing reference samples and thus providing a reliable genetic basis for the required morphological guidelines. I also tested gender markers, since hornbills exhibit a high gender dimorphism that also needs to be considered within morphological policies. Based on reference samples at the USFWS laboratory, I was able to identify markers that can be used to reliably determine both species and gender.

IEBR: I was able to use reference samples at the IEBR laboratory to test DNA markers that can be used to identify different species of salamander. The publicised markers had already been tested for other salamander genera, but not for all the salamander species relevant to this project. These markers can ultimately not only be used for identification purposes, but also to clarify the systematic relationship of species or for potential appraisal and distinction among populations (if more population samples can be obtained).

Privat

Analysis of a gender marker for hornbills (X = unknown gender; M = male bird; F = female bird)

Prospects

USFWS: I still keep in touch with the research group and, since more molecular identification tools are now available, we want to collect further samples from previously untested hornbills and then update the morphological guidelines, and possibly prepare a publication on the gender markers (should the latter occur, I will of course cite the DAAD scholarship). My abstract concerning gender markers in hornbills was included in a poster presentation by the Society for Wildlife Forensic Sciences (SWFS) in Kuala Lumpur (Malaysia) in 2024.

IEBR: Here too, I’m still in contact with the research group and we’re also working on a joint publication involving the morphological description of salamander species, including my section on the genetic components. Both research projects were conducted in certified wildlife forensic laboratories, so I additionally learned a lot about the composition and certification of a wildlife forensic laboratory and the handling of evidence. My hope for the future is to also establish such a certified wildlife forensic laboratory here in Germany and of course to continue conducting research in the domain of wildlife forensics. There are currently still some financing difficulties in this regard, but the researchers in the USA and Vietnam are more than happy to share their experience and answer all my questions. And when it subsequently comes to establishing a quality management system, which is a prerequisite for certification, I've now become familiar with some outstanding examples and points of contact. I’m also much clearer about the general processing sequence surrounding the chain of custody, for example, since in multiple cases I was given the opportunity to peer over shoulders and behind the scenes.

Privat

A Vietnamese salamander

USA: My contact with the USFWS laboratory arose through the SWFS Conference in 2022, which took place in precisely this laboratory. The host researchers were incredibly friendly and helpful with the preparations, such as project planning, obtaining a visa and other formalities. I didn’t have any issues with the visa or entry into the USA. It is however comparatively expensive in the USA, especially rent and food, although I could pay by card everywhere I went. The university had sadly not responded to any of my enquiries, the laboratory in Ashland is unfortunately not in touch with the university there, but is rather independent and belongs to the USFWS, so I booked airbnb accommodation and even this wasn’t a problem; I had a very nice one-room apartment that is around a 45 minute walk from the laboratory.

The monthly rent amounted to €1,976.17, which was comparatively cheap for Ashland, a very prosperous city in the USA. All the local researchers advised me not to use the public transport facilities (bus), since this wasn’t deemed to be safe for a young woman on her own. Other than that there wasn’t even a very good urban transport network, at least not in Ashland. I didn’t face any issues during my entire stay, but the following two addresses would have been useful in an emergency:

- Honorary Consul of the Federal Republic of Germany, 3900 SW Murray Blvd., Portland, OR 97005, USA

- Asante Ashland Community Hospital, 280 Maple St, Ashland, OR 97520, USA

Ashland features a beautifully landscaped park, Lithia Park, where I spent quite a few weekends. The city itself is a clean, nicely laid out small city in the USA where wild deer can often be seen running through the streets and front gardens. There are also some magnificent trails leading out of the city centre, such as to the Acid Castle Rocks from which you have a view back over the city. One Saturday, I also travelled with two colleagues to Redwood National Park in California, because Ashland is situated almost directly on the boundary to California. This was a superb excursion that I can only recommend – the sequoias there are considered to be among the tallest trees on the planet! Martin Luther King Day was also celebrated during my stay. It included transmission of a recording of the famous ‘I have a dream’ speech by Martin Luther King, Jr.

I didn’t face any language difficulties, other than once or twice when I used the British English expression for something and not the American English version. Albeit the laboratory staff are also very international in their orientation, so this wasn’t an issue. The food was very similar to what we know from Europe, apart from the corn syrup that seems to be present in almost all convenience products. A conversation with my local mentor revealed however that I wasn’t aware of ‘ice cream cake’ (a chocolate cake base with a thick layer of ice cream and cream on top), which forms part of a traditional birthday meal in the USA. She therefore ordered an ice cream cake during my last week and it was shared with everyone in the laboratory.

Privat

Right: Mozer in the laboratory and USA. Left: Samples in the IEBR Wildlife Forensic Laboratory in Vietnam

Vietnam: Contact with the IEBR laboratory was also established via the SWFS Conference in 2022. I was also in close contact with the researchers in advance of the research project, which meant that there weren’t any issues with my visa and entry. My preparations involved me learning Vietnamese every day for 200 days (using the free version of Duolingo with the result that I could learn more flexibly and at my own pace as opposed to a language course), which the local researchers also appreciated. This was also particularly advantageous when shopping at the market; you can easily get by with English in the main tourist areas, but away from the beaten tracks it was a great help if you at least had a basic command of the numbers and simple sentences in Vietnamese.

Prices in Vietnam are very reasonable from a European perspective; a bánh mì, a Vietnamese sandwich, generally costs € 0.70 and even the rent was very favourable. I lived directly opposite the institute and paid € 250.69 for two weeks. There isn’t much to see in this district of Hà Nội though, so in future I would sooner stay in the old district of Hà Nội and take a GrabBike taxi bike service to the institute, a journey lasting some 20 minutes, which costs a maximum of €1.50. I never drank the tap water in Vietnam, it is inadvisable throughout South-east Asia to drink tap water that hasn’t been boiled, since there are frequent cases of contamination caused by toxic industrial chemicals, heavy metals or pesticides, but also viruses and bacteria that can result in gastrointestinal disorders. Instead I only drank potable water from sealed bottles and again I didn’t face any problems. I did nevertheless have two useful addresses:

- German Embassy Hanoi, 29 P. Trần Phú, Điện Biên, Ba Đình, Hà Nội, Vietnam

- Thu Cúc International General Hospital, 286-294 Đ. Thụy Khuê, Thuỵ Khuê, Tây Hồ, Hà Nội 100000, Vietnam

Hà Nội is a magnificent city with an incredible number of attractions, but the highlights for me were Hoàn Kiếm Lake in which turtles used to live and around which the roads are closed every weekend to allow people to walk around the lake. Also the Temple of Literature, the oldest university in Vietnam! The night market in Hà Nội that takes place every weekend is also worth a visit. It is where you can try a wide variety of street food, including avocado ice cream, fried chicken feet, fresh fruit, eggnog coffee, and so much more. I was in general positively surprised by the food diversity; I requested the recipe for many dishes and have already tried to recreate some of them at home, including eggnog coffee and sốt vang, for example. My contacts with local researchers resulted in me being invited to visit the family of one researcher belonging to the Hmong people, an ethnic minority in Vietnam.

The village inhabitants were incredibly friendly. Despite the fact that the village is poor, everything was shared and everyone helps, celebrates and mourns with one another. The children led me around and showed me their school, taught me a few more Vietnamese terms, since they themselves didn’t speak any English, and in the evening everyone ate together and drank rice wine. A totally unique and wonderful experience!

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the host institutions, in particular Dyan Straughan and Hieu Tran, but also Jessica Oswald Terrill, Jen C. Tinsman, Ariel M. Woodward, Hope M. Draheim, Darren J. Wostenberg, Ed Espinoza, Mr Son, Ms Loan, Phang The Cong, Thomas Ziegler and Truong Nguyen for their readiness to actively help. I am also grateful to the DAAD-Stiftung’s Prof. Bingel Scholarship for giving me this unique and incredible opportunity and its associated experiences.

As of May 2024. The German version is the original.