Emily Belina

Privat

Privat

Emily Belina with Dr. Micheal Aven and his wife Linda York in a café

“I am incredibly grateful for the opportunity the Respekt & Wertschätzung Scholarship by the DAAD-Stiftung granted me, which was far more than one year of research funding. I was given a new perspective, new community, and a new life I never knew to imagine.”

US biologist Emily Belina came to Germany to research extracellular vesicles and their involvement in diseases at the Johannes Guttenberg University in Mainz. She was also enthusiastic about Mainz and its surroundings. This was made possible by the Respekt & Wertschätzung Scholarship.

Here she describes her research in the laboratory, her experiences in Rhineland-Palatinate and beyond, her connection to her sponsor and much more:

With the support of the Respekt and Wertschätzung Scholarship, I was able to conduct research in the May-Simera lab at the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz. For two years I have been investigating ciliary signaling in this lab, building on work I completed during my undergraduate studies in the US.

The scholarship allowed me to focus on the role of extracellular vesicles (EVs) in congenital ciliopathies. Primary cilia are signaling organelles found on the surface of most cells in vertebrates, including in tissues in the eye. Genetically induced defects in the primary cilium often lead to severe disease phenotypes, called ciliopathies. Though primary ciliary are typically thought of as mainly receiving signals, the presence of ciliary EVs indicates they could also be releasing information.

Privat

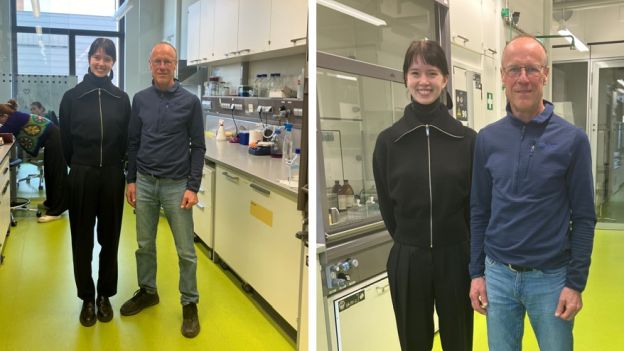

Emily Belina and Michael Aven tour the lab

EVs are a major new area of research, and previous publications from the May-Simera lab have demonstrated that primary ciliary EVs could contribute to such ciliopathies. Despite EVs’ potentially critical role, their mechanism and function remain understudied. This past year, I focused on further investigating the contents of EVs derived from ciliopathic cell lines, and whether they can elicit a response, looking in particular at protein homeostasis.

The field of EVs is still in a stage of growth, meaning many existing commercial bioactivity assays are neither designed nor tested for the peculiarities of EV experiments. I worked with EV isolation protocols from the May-Simera lab in order to adapt an assay kit to such experiments.

I was eventually able to develop a reproducible protocol for the lab to use for all future EV protein homeostasis work. I additionally produced incredibly compelling data related to the contents of EVs that has major implications for our understanding of ciliopathic disease mechanisms. A more accurate understanding of the disease mechanism will make it eventually possible to develop a treatment for these ciliopathies.

Privat

Impressions of the cathedral square and Mainz Cathedral

One such ciliopathy is Bardet Biedl Syndrome (BBS), often called the archetypal ciliopathy, since affected individuals present with nearly every ciliopathic phenotype. The principal investigator of the lab, Dr. Helen May-Simera, has a close working relationship with members of the BBS society, a group for individuals with BBS and their families.

Some of my most valued memories from this past year were from being able to meet these families and learn from their lived experience when they visited Mainz. One recently graduated high schooler with BBS even spent a week in the lab with us learning basic protocols. Such opportunities feel incredibly rare in research and yet are necessary to contextualize microlevel techniques and papers with the full humanity and experience of individuals living with ciliopathies.

Privat

Views of Mainz city center and the Christmas market

My previous lab work prepared me well for the research in Germany, and given the international nature of scientific research, there were no major cultural differences within the lab that I needed to overcome. The May-Simera lab at the University of Mainz was a particularly welcoming environment.Dr. May-Simera, the PhD and master’s students, and the post-doctoral researchers all create a culture of collaboration and mutual support.

No matter how busy someone was, they would always patiently show me where a certain chemical was or explain part of a protocol. Upon my leaving the lab, they even gave me a recipe book from a bakery in Mainz I had once mentioned was my favorite. Though I was only there for a short period, the members of the lab took the time to get to know me and make me feel at home in a place so far from home.

Outside of working hours, members of the lab frequently got together for group dinners, hikes, football games, and, when the season was right, visits to the Christmas market. My sponsor, Dr. Michael Aven, also came to visit the lab for a tour and dinner on campus, which was an exciting opportunity to meet the person making my research possible.

Privat

The Hochheim am Rhein vineyards

I started my research in Germany as a gap year, with the intention of returning back to the US for medical school. When I first arrived in the country, my German language skills were extremely limited and I initially felt overwhelmed even just stepping outside to go to the grocery store. In my neighborhood, residents frequently tried to start conversations if we were both waiting at the bus stop. Though it took me half a year to start to understand them, I quickly became very good at having entire conversations just by nodding and pretending I knew what they were saying.

Immersion is undoubtedly the best way to learn a language, however, even when someone has little to no base knowledge, such as in my own case. I was soon able to fully participate in these conversations, and once I learned how to properly separate my recycling and to remember to go grocery shopping on Saturday before the stores close on Sunday, I began to feel at home in Germany.

Privat

Two Mainz originals: the carnival parade and Gutenberg's printing press

The college town feeling of Mainz quickly allowed me to meet friends both German and international. After two years of living, working, and building community, I ultimately decided to move to Germany permanently and attend medical school here. After passing my language exam and successfully making it through the application process, I am proud to announce I am now starting my studies in Humanmedizin at the Universität zu Köln.

I plan to continue research in ophthalmology during my studies and beyond, using both my language abilities and contacts in the US and Germany to facilitate collaboration between researchers. I am incredibly grateful for the opportunity the DAAD-Stiftung scholarship granted me, which was far more than one year of research funding. I was given a new perspective, new community, and a new life I never knew to imagine.

As of October 2024.